Community vision – the future

Theme 9. Homes and planning

LLTTNP identifies Callander as a ‘key placemaking priority site’. The town can provide access to key public services and has some infrastructure capacity.

LLTTNP’s 2017-2024 Local Development Plan (LDP) and their Callander South Masterplan Framework allocated land for up to 148 houses with provision for some infill site development. It proposed a major greenfield site development of 90 homes at Claish Farm and envisaged a further 100 longer-term.

Since the LDP came into force, 77 affordable rented homes have been built and occupied: 50 at Claish Farm, 23 at Station Road, and four at Pearl Street. Another new-build development of four flats is privately owned.

The LDP also marked Claish Farm for economic development, a playing field and visitor experience. For long-term visitor experience development it highlighted Claish Farm, again, along with Gart Farm.

The LDP proposed retail and business development in the Station Road Car Park alongside the site’s existing parking and transport functions.

A revision of the Callander South Masterplan Framework was due in March 2022 but had not yet been approved by the time the final community consultation closed. In August 2022 advance notice was given of major residential development on the Mollands Farm, another greenfield site.

Callander has a profound sense of place. Its vernacular architecture contributes significantly to our town’s attraction to residents as well as tourists.

The ‘identikit’ nature of new housing developments does not reflect any elements of the local vernacular. Planners have permitted elevated rooflines on new-build properties that dwarf nearby traditional houses.

New development has not addressed the needs of people living with disability or older residents seeking to downsize.

Social housing constitutes 23% of all homes in Callander, and the town now has the largest social housing provision in the National Park. Despite the ratio of social to private housing, local people and families struggle to find affordable housing in the town. This problem has been exacerbated by increases in property prices over the past two years and by homes being turned into holiday lets.

In the past decade the climate emergency has manifested in Callander as more frequent flooding events and warmer, wetter, winters. LLTTNP policies do not set clear standards around climate-friendly housing design, they only ask that developers ‘consider incorporating zero carbon technology into your building designs.’ It is hoped that LLTTNP will revise their position on environmentally sustainable housing development ahead of guidelines in the draft NPF4.

Solutions

i. Affordable homes for Callander residents

Planning and development policy should require housing developers and social landlords to provide a mix of low-cost starter homes, rent-to-buy, and/or shared ownership properties. This policy has local precedent. In 2000, 15 low-cost private homes were built in Callander for those on the housing waiting list.

ii. A wider range of new homes

New developments of multiple homes in Callander should provide a range of options to cater for the various stages in people’s lives. They should address the needs of people who are single, new families needing starter homes, larger families, those who need to downsize, and people with disabilities who need accessible homes with room for equipment and carers.

iii. Sense of place

New-build development in Callander should be designed with future adaptability, climate change and resource efficiency in mind.

Any new-build property should respect our topography, views, and skylines as well as the wider landscape. Design and density should complement its surroundings in terms of height, scale, materials, and finishes.

iv. Protecting our natural assets

There should be no new residential or commercial development or quarrying on, or close to, Callander’s unique geological features (including the eskers and moraine), the SSSIs, GCRs or SAC, or land identified as being at risk in SEPAs 2080 Flood Future maps.

v. Holiday lets

All new-build private homes should be subject to a burden stipulating that they cannot be used as holiday or short-let accommodation for at least ten years after completion.

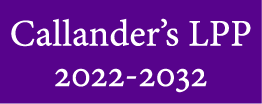

Figure 6. Callander’s protected natural environment sites

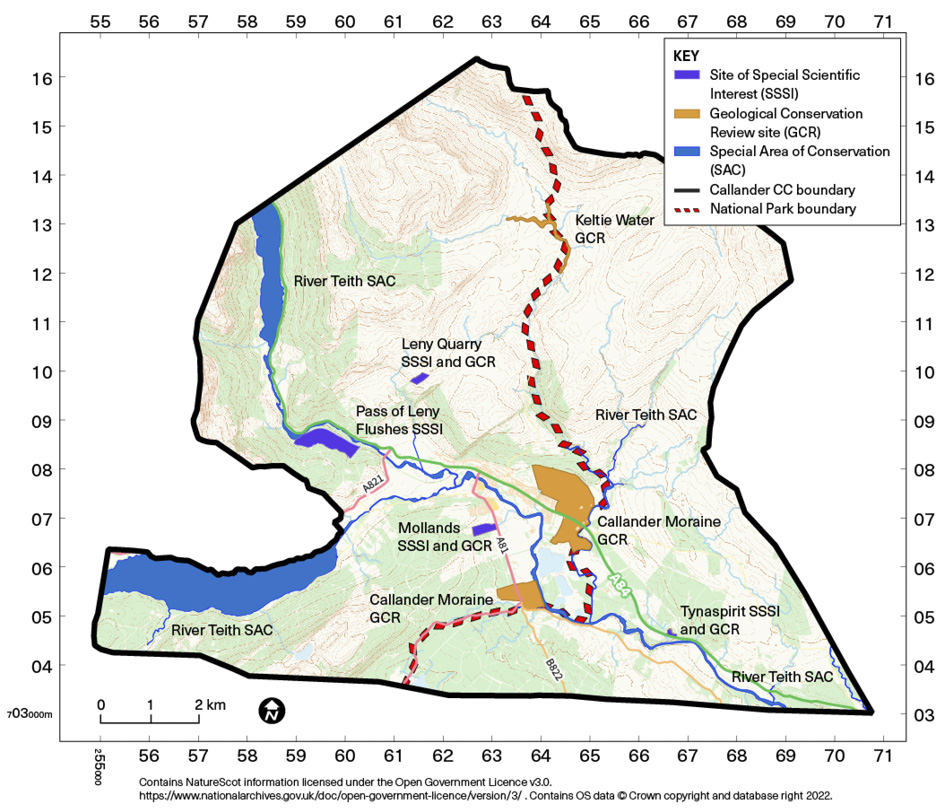

Figure 7. Sketch map of Callander’s Loch Lomond Stadial geosites in context

2. Thompson, K.S.R., 1972. The Last Glaciers in Western Perthshire. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh. https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/27530. Lowe, J. and Brazier V., 2021. The Callander (Auchenlaich) moraine: A new site report for the Western Highland Boundary block of the Quaternary of Scotland Geological Conservation Review (GCR). In: Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association.132 (2021) 24-33. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2020.09.005 . Merritt, J.W., Coope, G.R. and Walker, M.J.C., 2003. The Torrie Late Glacial Organic Site and Auchenlaich Pit, Callander. In Evans, D.J.A. (Ed.), The Quaternary of the Western Highland Boundary. pp. 126–133 Quaternary Research Association..

Click here to return to where you were in the main text.

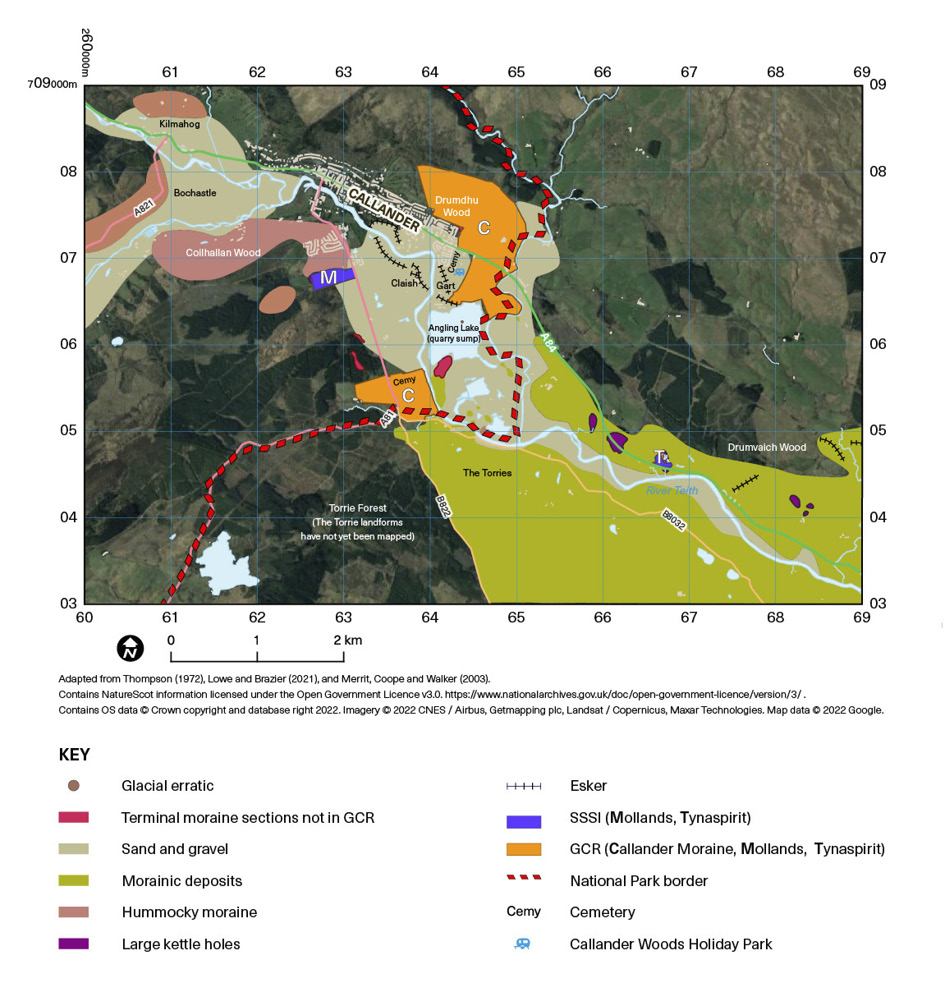

Figure 8. The Callander Moraine GCR, Mollands SSSI and GCR and associated glacigenic landforms in detail

3. Merritt, J.W., 2015. Teith valley and Strathallan. In: Browne, M.A.E., Gillen, C. (Eds.), A geological excursion guide to the Stirling and Perth Area. Edinburgh Geological Society, pp. 103–116. https://earthwise.bgs.ac.uk/index.php/Teith_valley_and_Strathallan_-_an_excursion . Tisdall, E. and Miller, A.D., 2022. Recognising geodiversity and encouraging geoconservation — Some lessons from Callander, Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park, Scotland. In: Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2022.08.001.

Click here to return to where you were in the main text.